| Activity | Time Required (approx) |

| Blog post | 3-5 minutes |

| Activity | 10 minutes (+ optional extra activity). |

Librarians and TEL Advisors encounter some really neat tools that have a broad application. One such example is Creative Commons licences. We shout about these wherever we can, yet we are continually surprised that relatively few colleagues across the university – and further afield – have heard of them, or know what they do.

What are they?

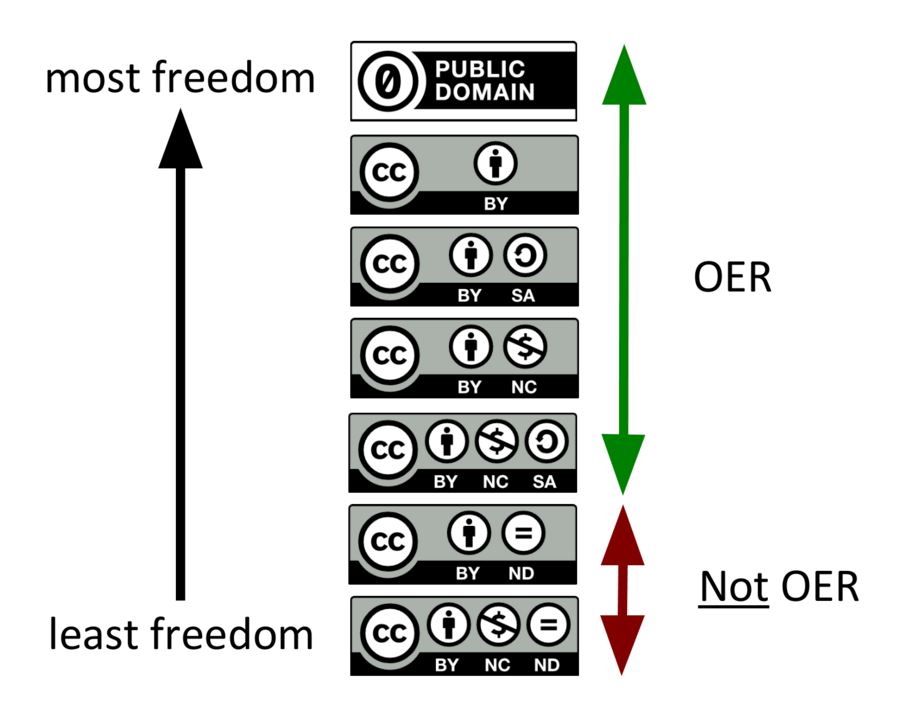

They are legally enforceable licences that allow the owner of a copyright work to release that work to others to reuse, subject to certain conditions. The most permissive licence allows works to be adapted, altered and remixed. Others will allow retention and reuse only. It is arguable that to qualify as an OER, a work must allow revision and remix. This handy graphic explains the thinking behind this:

A bit of history: the Creative Commons organisation was founded in 2001 by three US academics. The first licences were released in 2002, and as of 2015 there are over 1 billion Creative Commons licensed works worldwide.

What can be released and reused under Creative Commons licences?

A huge variety of digital content, for example: text, videos, images, presentations, webpages, blogs.

If you are a researcher and you plan to publish your work, it is likely you will encounter Creative Commons in the not too distant future. It is becoming increasingly common for publishers to offer to publish your work open access and make it available under a licence. More on this in day four!

Copyright law and Creative Commons: is there a difference?

Creative Commons complements copyright law; however, there is a distinction between using something under licence vs. under an exception in law. In the UK we have a number of fair dealing exceptions which might permit you to use a small portion of a work for a certain purpose without needing to rely on a licence. A full summary of the copyright exceptions can be seen on page 12 of the ILS copyright booklet.

Public domain works can be freely used by anybody. These items are no longer in copyright either because the copyright has expired (typically if the author died more than 70 years ago) or because the copyright owner has waived the right to their work.

A summary of the different licences:

There are six licences with different conditions attached. You can read about them on the Creative Commons page – and here is a handy summary:

CC BY: attribution only. This is the most permissive of all the licences. It allows anybody to share, remix and build upon your work, including for commercial purposes. They must always credit you for the original creation.

CC BY: attribution only. This is the most permissive of all the licences. It allows anybody to share, remix and build upon your work, including for commercial purposes. They must always credit you for the original creation.

CC BY-ND: attribution, no derivative works. This licence allows others to share your work, including for commercial purposes, so long as they do not change it in any way. They must always credit you for the original creation.

CC BY-ND: attribution, no derivative works. This licence allows others to share your work, including for commercial purposes, so long as they do not change it in any way. They must always credit you for the original creation.

CC BY-NC-SA: attribution, no commercial use, share alike. This licence allows others to share, remix and build upon your work, but they cannot use it for commercial purposes. They must licence their new creation under identical licence terms. They must always credit you for the original creation.

CC BY-NC-SA: attribution, no commercial use, share alike. This licence allows others to share, remix and build upon your work, but they cannot use it for commercial purposes. They must licence their new creation under identical licence terms. They must always credit you for the original creation.

CC BY-SA: attribution, share alike. This licence allows others to share, remix, and build upon your work, including for commercial purposes. They must licence their new creation under identical licence terms. They must always credit you for the original creation.

CC BY-SA: attribution, share alike. This licence allows others to share, remix, and build upon your work, including for commercial purposes. They must licence their new creation under identical licence terms. They must always credit you for the original creation.

CC BY-NC: attribution, no commercial use. This allows others to share, remix and build upon your work, but they cannot use it for commercial purposes. They must always credit you for the original creation.

CC BY-NC: attribution, no commercial use. This allows others to share, remix and build upon your work, but they cannot use it for commercial purposes. They must always credit you for the original creation.

CC BY-NC-ND: attribution, no commercial use, no derivatives. This is the most restrictive of all the licences. It only allows others to download and share your work with others, but they cannot change them in any way, or use them for a commercial purpose. They must always credit you for the original creation.

CC BY-NC-ND: attribution, no commercial use, no derivatives. This is the most restrictive of all the licences. It only allows others to download and share your work with others, but they cannot change them in any way, or use them for a commercial purpose. They must always credit you for the original creation.

Also!

You can use CC0 if you’re the copyright owner and wish to assign your work into the public domain, or the Public Domain Mark can be used to denote a work that is free of known copyright restrictions.

You can use CC0 if you’re the copyright owner and wish to assign your work into the public domain, or the Public Domain Mark can be used to denote a work that is free of known copyright restrictions.

Reference resources…

Creative Commons website: https://creativecommons.org/

Cushing, T. (2015) Photographer loses copyright infringement lawsuit against mapmaker that used his photo with his explicit permission – this is a useful example of Creative Commons being defended in a court, and demonstrates the importance of paying attention to licence conditions!

Ruth MacMullen: York St John University’s Systems Support & Library Compliance Officer, and your personal copyright and licensing resource! 🙂

Activity

You’re giving a lecture and want to brighten it up with a picture of your favourite animal. Do a search for it on Wikimedia Commons. Once you’ve found your image, look at the licence terms. Post a link to the image, along with the licence name and what it would allow you to do with that image. Include a full attribution to the author.

Optional further activity:

You have published a research paper with a well-known journal. They are offering two licences: CC BY, or CC BY-NC-ND. What would affect your decision over which licence to choose? Some examples:

- How much control would you retain over your work?

- How much impact would you like your work to make?

- Who do you want to have access to your work? Would the NC (non-commercial) clause exclude any uses or organisations that should be allowed?

Complete at least three activities across the five days to earn our ‘Open Education Enthusiast’ badge.

Still to come…

- Day 4: Introduction to Open Access Publishing

- Day 5: Becoming an Open Educational Practitioner

Don’t forget to follow us on Twitter at @YSJTEL and @YSJ_ILS or search the hashtags #YSJOpenEd and #OpenEdWeek for additional materials or comment.

Róisin Cassidy (Technology Enhanced Learning),

Ruth MacMullen, Ruth Mardall and Clare McCluskey-Dean (Information Learning Services)

| <<< Day 2: The ‘What’, ‘Why’ and ‘Where’ of Open Educational Resources | Day 4: Introduction to Open Access Publishing >>> |

8 responses on "5 Days of Open Education – Day 3: Creative Commons Licensing: know your SA from your ND!"

Leave a Message

You must be logged in to post a comment.

By Christian Mehlführer, User:Chmehl (Own work) [CC BY 2.5], via Wikimedia Commons

Here is a link to the picture of a Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens)

Licence is CC BY-SA 3.0, allowing me to share and remix this picture if I ensure that I attribute the work to its author (not machine-readable source provided, Brunswyk assumed). Any modified picture will be shared under the same licence CC BY-SA.

Image of a penguin https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/de/Imperador_2p.jpg

CC BY-SA: attribution, share alike. This licence allows me to share, remix, and build upon my work, including for commercial purposes. They must licence their new creation under identical licence terms. They must always credit you for the original creation. Author is Postpr

Here is a picture of a giraffe – my favourite animal. https://pixabay.com/en/giraffe-zoo-animals-556023/

I tend to use pixabay.com for images – this are;

CC0 Public Domain

Free for commercial use

No attribution required

I tend to also attribute to them in my blog – stating that the original image is from the site.

I would always want my research to be in the public domain and let everyone have free access to it.

Link to Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Felis_silvestris_catus#/media/File:Catstalkprey.jpg

License is CC-BY and would allow me to share the image in any form, and to adapt and remix the image for any purpose – even commercial.

Optional Activity: In the case of a research paper bearing my name, I would prefer to use the CC-BY-NC-ND. The principal reason for this is that I would not want others to change any part of the research paper since that could affect its integrity and authenticity. An unscrupulous person could make changes in the reported data, methodology, results, conclusions or all of the above and arrive at a completely different (and fraudulent) research paper – and it would still have my name on it.

Hi Peter, this is a common and very understandable concern. It’s worth noting that when you use any Creative Commons licence you retain moral rights to your work. These include the rights to not have your work treated in a derogatory manner, or to have false works attributed to your name. So if you used a CC BY and somebody made changes that affected the integrity of your work, it’d be a matter of law rather than licence.

I had problems accessing Wikimedia Commons on my PC so couldn’t complete the task – although several attempts were made.

In terms of the other suggested tasks, here are my comments regarding different types of licenses for a journal article:

If I had recently published an article in a journal and was thinking about different types of licenses I would consider the following factors:

I would like the article to primarily reach other academics/institutions so perhaps would ask if the CC BY-NC-ND license could enable this type of access whilst restricting commercial re-use. Whilst in theory it would be great to reach a wider audience as possible, the CC BY license would mean that others could potentially use the article for their own commercial gain, or edit/change the material and the data presented.

Here is a picture of a cat that looks a lot like one of mine: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Atento_(9408095357).jpg This picture is CC BY 2.0 and I can share or adapt the image, even for commercial gain, as long as I ensure that I attribute the picture to the originator (Juanedc from Zaragoza, España), provide a link to the license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en) and indicate if changes have been made (they have not).

Optional activity: In this example, in terms of which license I would use, it would be the CC BY as I would prefer my work to make the maximum impact possible. I don’t like the idea that someone could use the entirety of my research for their commercial gain, however, and generally speaking I would prefer to use the CC BY-NC license.